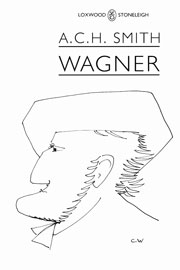

Book cover featuring a cartoon of Richard Wagner by Charles Wood

Wagner

Novelisation of Charles Wood's screenplay

ISBN 978-1-85135-035-3

About this book | Read an excerpt | How to buy this book

The great thing about Tony Palmer's film is that, on its epic scale, it takes over from real life and makes you submit totally. Richard Burton was the very embodiment of Wagner. This film is one of the truly great experiences of the cinema. - The Guardian

Wagner is a novelisation of Charles Wood's brilliantly imaginative screenplay, written in the early 1980s.

Directed by Tony Palmer, the film starred Richard Burton, in his last major role, and Vanessa Redgrave, and uniquely brought together the three knights,

Olivier, Gielgud, and Richardson.

Richard Hornak, in Opera News, found it to be one of the most beautiful motion pictures in history.

It was produced with a running time of seven hours and 46 minutes (read more here in Wikipedia).

Wagner film, directed by Tony Palmer, screenplay by Charles Wood, 1984.

Translations of the book were successfully published in Germany and Italy, where the film was serialised on TV. But even though the film has been available on VHS & DVD for the last 30 years, the book remained unpublished in the UK. Now that the film has been remastered in Hi-Definition*, in time for the 200th anniversary of Wagner's birth, the novelisation is at last available in the language in which I wrote it.

(*3 DVDs, in wide-screen stereo as it was first edited by the director in 1983. From Gonzo Multimedia, www.gonzomultimedia.co.uk/Wagner, and from all good record shops.)

Wood, a brilliant dramatist, advised me: "Take outrageous liberties. I did." So I did. His response to reading the novelisation (after waiting 30 years) was:

I love it. You have done an enormous amount of work and research outside of the confines of the screenplay - and it all fits, indeed it has given me a good few ideas about how the next version of it might go. It would be terrific on the stage.

It's so funny. It'll keep me chuckling gently to myself. By God you nailed him. And oh the swing of it, the swing of it ... perfect. What wonderful work you have done, dear friend. (I felt just like the Master there, sorry.) Here's to the success of it and its reprinting in glorious glossy huge colour. All those castles and swans and big fat Rhine Maidens ...

Excerpt from Wagner

Wagner was listening with pleasure to the Dante Symphony, but on the farther side of the piano Minna was unable to concentrate on the music. She was preoccupied with Karl Ritter, who had sat next to her throughout the recital glaring with unrelenting hatred at the pianist. He had made no secret of his grievances. 'My dear Frau Wagner,' he murmured to her, 'I will demand and receive an apology from that man.'

'Karl,' Minna whispered, 'you must not act so. Liszt is the mildest, the gentlest of men. He would not dream of insulting you. You must have been mistaken.'

Karl was not to be deflected. 'I was not mistaken. He called me a baboon. I have communicated the dreadful humiliation to my mother. Baboon face...' Karl snarled quietly.

The Dante Symphony was nearing its end. Anxious to prevent a scene, Minna tried another tack. 'Karl, surely - a moment of ill humour, it isn't as important as all that, surely not?'

'It is,' Karl answered, suddenly having to shout above the applause. 'It is, it is!'

Wagner had risen from his chair, clapping warmly, and was coming across to speak to Minna.

'It is,' Karl insisted, 'Frau Wagner, I am about to marry. I cannot be treated in such a way.'

'Marry?' Wagner asked in surprise, having overheard Karl's shout. 'Are you absolutely convinced that that would be wise, Ritter?'

Karl gasped, 'Ohhh!', and stormed away to the far side of the ballroom, his jaw quivering.

Mathilde had addressed the gathering, with the announcement that by telegraph from Weimar a poem had been received. It had been written in honour of Liszt's birthday, and would be read to them now by one of Zürich's own foremost poets, Georg Herwegh. While the latter's natural baritone modulated unsurely into a poetry-reading tenor, Minna was whispering urgently to her husband. 'Karl is really most upset, Richard.'

'Is he?' Wagner was not listening to Minna, nor to the poem. He was looking at Mathilde Wesendonck, who had just spoken so charmingly to them all.

'It's most unfortunate, most,' Minna was whispering. 'You see, when he was a boy - he explained this to me - he was teased mercilessly about his appearance, and the most wounding taunt of all used to be "baboon face."'

'Did it?' Wagner was still not listening.

'So you can see why Liszt has...'

Minna was cut short by another burst of applause, for the end of the poem. Wagner led the clapping, beaming as he did so at Mathilde, and at Otto beside her, whom he caught stifling a yawn. A buxom, golden-haired soprano, Frau Heim, was standing beside Liszt at the piano, with a manuscript in her hand. The fond look on her face was for Wagner, who was to join her in a recital performance of a passage he had recently sketched for the Valkyrie. As he turned to join Frau Heim, Wagner muttered to Minna, 'The young fool isn't going to mount an exhibition of his foolishness, is he?'

Minna shrugged, with dismay. How was she to know? Also, she would have liked to say under different circumstances, she had noticed the fluttering eyelashes that Frau Heim directed at her husband, but whether their welcome was more than musical, how was she to know?

To turn his music for him, Liszt had Hans von Bülow at his side. Wagner had the greatest confidence in Bülow; not only was he a protégé of Liszt, and affianced to Liszt's daughter Cosima, but the fine young fellow had made himself a virtual outcast from the musical world of Berlin through his passionate championing of Wagner's music. Again and again, in articles entitled, 'Art and Revolution' or 'The Art-Work of the Future', he had assailed with unhoneyed words the aunties, the dotard critics, whose delusion it was that Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn had ever written a note worth hearing. He had arrived in Zürich with the news that the battle was raging ever hotter. Wagner had a warm pat on the shoulder for Bülow as Liszt led them into the Valkyrie.

While he sings, knowing it so well, Wagner has time to keep an eye on the audience. He notes Wesendonck stifling another yawn, thereby attracting a cross glance from his wife Mathilde, and rallying his attention to look up at the performers, where he meets Wagner's basilisk eye, and confusedly lowers his gaze again. Near the Wesendoncks are an older couple, also patrons of the arts, but who seem to have no difficulty in listening to the art they patronize: Doctor Wille, whose views on politics are as pugnacious as his scarred face testifies his private life has been, and Frau Wille, irredeemably plain, but an intelligent and cultivated hostess of the salon. She is a particular friend of the striking figure leaning on the end of the piano and smoking a cheroot, the Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein, thin and thirtyish, Liszt's mistress but not to be his wife unless the Vatican grants the Prince a dissolution. People have remarked that the Prince, having been married to Princess Carolyne, is no stranger to dissolution already, but people will always make remarks of that sort at the sight of a blue stocking. With an encouraging glance at Frau Heim, in her aureole of golden hair, Wagner sounds the Motive of Renunciation, Zum letzten Mal letz' as mich heut mit des Lebewohles letzteng Kuss, and notes Mathilde's rapt expression, and also Karl Ritter edging toward the piano, where Liszt has the look on his face of a man who would by now be playing with his eyes closed in ecstasy had he performed this music just once before in his life.

The moment they finished there was a burst of applause and bravos. Karl had seen his chance, but the most admirable Bülow had seen Karl even more quickly, had intercepted his lurching grievance, and was firmly leading Karl away. Wagner, under congratulations from Doctor and Frau Wille, had beady eyes. He was watching the idiot Ritter, who appeared to be safe for the moment in Bülow's hands, and he was watching Mathilde, whose opinion would be relishable. She, slowly followed by Wesendonck, had engaged Liszt and the Princess Carolyne in an earnest conversation, from which she hoped to draw cultural sustenance more substantial and worldly than the common fare in Zürich.

'Heine?' She picked a name, hoping that Liszt, with his urbanity, would make her a meal of it.

But Liszt, who had had a tiring day, looked along his fine nose at Mathilde, and merely repeated, 'Heine?'

Mathilde had to explain herself. 'Has the poet Heine, the great German poet Heinrich Heine...'

'Madam,' Liszt began politely, 'I am aware...'

'Heine?' Princess Carolyne exclaimed.

'Heine,' Mathilde persevered, knowing that she would not forgive herself if she let this opportunity slip for want of a predicate, 'has Heine been of any influence in Herr Wagner's...'

'Wagner?' Princess Carolyne shrieked at the stupidity of this woman. 'It is the birthday of Liszt!' She snorted and sucked at her cheroot. 'Heine... Wagner...'

Wishing to extricate the poor creature, of a type he had suffered after thousands of recitals, Liszt made use of consummate mendacity. 'I have the highest regard for the poet...'

Princess Carolyne puffed smoke. 'We think very little of the poet Heine.' Why should she bother to explain to this pretentious housewife that the poet Heine in his guise of musical critic had practised upon Liszt a version of simony, showing him the manuscript of a spiteful review and, upon receiving no bribe, increasing its spite for publication?

Over her lovely shoulder, Mathilde cast an agonised look at her husband. He wisely refused to be drawn into the circle of hell she had made for herself. He stroked his beard, and pretended to be interested in the piano.

Wagner had decided that he must urgently settle Ritter's hash. Crossing the crowded room, accepting homage piecemeal, he reached the epicene booby. 'Karl, you must not make a scene. Look, I will undertake to speak to Liszt and make your feelings known to him. I'm sure he will wish to express his regret for them, in his own way, by letter perhaps, mmm?'

Karl was primed. 'I shall demand an apology now. If he refuses, you will not get another pfennig from my mother.'

Wagner put his hand on Karl's shoulder, and looked at him painedly. 'Wait,' he said. He crossed the floor again, to where Mathilde was still struggling to make a conversation with Liszt and the Princess. The great pianist's nostrils were quivering. 'Why do you keep on about Heine?' he complained. 'I don't want to talk about Heine.'

'But surely,' Mathilde plunged on, 'his name will be inscribed in the temple of immortality?'

'I suppose it will be,' Liszt snickered, 'in mud.'

Bowing to Liszt and the inevitable, Mathilde left, followed by Wesendonck. Wagner watched her go, then drew Liszt aside to whisper in his ear. Princess Carolyne also inclined her head to hear what Wagner had to say. She was not in favour of secrets.

Karl, slowly approaching, watched the scene with satisfaction. Minna, too, sighed with relief when she saw Liszt nod, and Wagner look up and beckon Karl.

As Karl drew near, Princess Carolyne shook her head in puzzlement. 'Are we not making too much of it?'’ she asked Liszt quite loudly. 'After all, the boy does look very like a baboon, does he not?'

Karl turned away, with a twitching face, and hastened to leave the ballroom. At the door, a footman handed him a commemorative medallion with a portrait of Liszt on it.

How to buy this book

To purchase a copy of Wagner, please email ach@achsmith.co.uk

Price £10, plus p & p: UK £1.50, Europe £4, elsewhere £7.